Does West Side Farming Make Economic Sense? (Part 1)

Friday, March 26th, 2010Water supplies for West Side agriculture have been major news items in the past few years. Many residents, including this writer, are proud of our agricultural heritage and bounty, and have questioned decisions that threaten water supplies for agriculture.

Journalist and attorney Lloyd Carter has penned a provocative article that probes the financial integrity of Westside agriculture.

Mr. Carter’s thesis is that, “While Westlands . . . has produced an undisputable bounty of cotton and field crops over the decades in western Fresno and Kings counties, irrigation of this mineral-laden desert has also created huge environmental problems, and the wealth generated has not trickled down to farmworkers or the surrounding poverty-stricken communities.”

Early West Side Farming

Mr. Carter admirably recites the history of West Side farming. “In 1900, the West Side of the Valley remained an inhospitable desert with no surface water and only intermittent flow from small seasonal creeks . . . The first wells in western Fresno County were sunk a few years after the start of the twentieth century by a few hardy pioneers. Deep wells were drilled during World War I by large landholders in order to plant cotton, a salt-tolerant crop in demand by the military.”

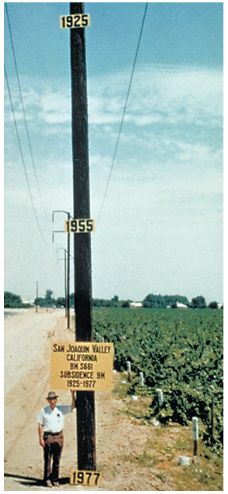

Take a look at this remarkable photograph, which shows researcher Dr. Joseph F. Poland standing at the location of maximum land subsidence identified in the Central Valley. The signs on the pole show the approximate altitude of the surface of the land in 1925, 1955, and 1977. The site is in the San Joaquin Valley southwest of Mendota, California.

Take a look at this remarkable photograph, which shows researcher Dr. Joseph F. Poland standing at the location of maximum land subsidence identified in the Central Valley. The signs on the pole show the approximate altitude of the surface of the land in 1925, 1955, and 1977. The site is in the San Joaquin Valley southwest of Mendota, California.

The level of the earth subsided by more than 28 feet at this location near benchmark S661 southwest of Mendota, due to the pumping of groundwater.

More information can be obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey.

And from this article:

“Land Subsidence in the United States,” by Devin Galloway, David R. Jones, and S.E. Ingebritsen

In 1942, West Side growers, who were running out of groundwater, formed the Westside Landowners Association to gain support for federal assistance in delivering Northern California river water to their region.

In 1952, pursuant to the California Water Code, the growers formed the Westlands Water District, which would grow to become the nation’s largest federal irrigation district, with over 600,000 acres.

Bernie Sisk’s False Promises

Carter continues. ”In 1959, Representative Bernard F. Sisk (D-Fresno), who represented the Westlands area, pushed for congressional approval of a U.S. Bureau of Reclamation project to deliver Northern California water to Westlands.”

In 1960, Congress approved the San Luis Unit. Water deliveries to Westlands began in 1968.

Now, if you live in Fresno County, you will be astonished that Rep. Sisk made the following representations to secure Congressional approval for the water project. Here’s what he promised:

- “If San Luis is built, according to careful studies, the present population of the area will almost quadruple. There will be 27,000 farm residents, 30,700 rural nonfarm residents, and 29,800 city dwellers; in all, 87,500 people sharing the productivity and the bounty of fertile lands blossoming with an ample supply of San Luis water.”

- “Recent surveys show that the land proposed to be irrigated is now in 1,050 ownerships. These studies show that with San Luis built, there will be 6,100 farms, nearly a sixfold increase. And in the breaking up of farms to family-size units, anti-speculation and other provisions of the reclamation laws will assure fair prices.”

We can all pause here. Westlands was built on a false premise. Nothing close to this has occurred in the past half century.

Where Are We?

“This Article shows how a long American tradition of helping small farmers has, in the past few decades, morphed into a massive government aid program for large industrialized agribusiness operations-a program that not only drives small farmers off the land but also perpetuates rural poverty because agribusiness requires huge numbers of low-paid, seasonal harvest workers”

Part 2 – Continued next week.

Lloyd G. Carter, Reaping Riches in a Wretched Region: Subsidized Industrial Farming and its Link to Perpetual Poverty, in 3 Golden Gate U. Envtl. L.J. (2009) page 5.