We’ve Been Taken for A Ride

Saturday, May 29th, 2010It may be time for average persons to stop investing in the stock market. I’ve been a big believer in the market over the years, and am familiar with the statistics showing how stock market investments have grown over the years.

But the evidence is mounting – and may now be overwhelming – that shows that the big players have rigged the markets.

First, flash trading a.k.a. computerized trading controls the stock market these days. The stock exchanges TAKE MONEY to allow traders to hitch their computers closer to the computers used by the stock exchange.

The weird gyrations in the market are driven by computerized traders that make a little going up and a little coming down, as long as the trades keep happening. For example, Goldman Sachs makes most its income from trading. Trading your stocks. For its own benefit.

“Goldman made $3.5 billion in profits in just three months. While it doesn’t break down profits in detail, it does give a broad sense of where its revenues come from. Just $1 billion or 8 percent, came from traditional investment banking. The biggest slice, 72 percent, came from trading. Morningstar analyst Michael Wong says that trading category covers a wide range of activity.”

“What we do see is a trend which has been developing over the past few decades. Goldman Sachs and the other investment banks are making more money making trades than they do doing the things investment banks traditionally do.”

The part that makes this all crazy is the hidden derivatives market. As Matt Taibbi recently reported (Rolling Stone – May 26, 2010), “This insane outgrowth of jungle capitalism has spun completely out of control since 2000, when Congress deregulated the derivatives market. That market is now roughly 100 times bigger than the federal budget and 20 times larger than both the stock market and the GDP.”

Try to get your arms around that point. The derivatives market is 20 times larger than both the stock market and the GDP.

Gary Gensler, chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, described the problem as follows at a June 2010 exchanges conference in New York: “The buyer and seller never meet in a centralized market. Right now, when Wall Street banks enter into derivatives transactions with their customers, they know how much their last customer paid for the same deal, but that information is not made publicly available. They benefit from internalizing this information.”

Taibbi also reports that “Five of America’s biggest banks (Goldman, JP Morgan, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley and Citigroup) raked in some $30 billion in over-the-counter derivatives last year. By some estimates, more than half of JP Morgan’s trading revenue between 2006 and 2008 came from such derivatives.”

That is simply insane unregulated capitalism. Your 401k account goes into the tank, the stock market experiences unprecedented gyrations, and the big players make money hand over fist, at your expense.

“Imagine a world where there’s no New York Stock Exchange, no NASDAQ or Nikkei: no open exchanges at all, and all stocks traded in the dark. Nobody has a clue how much a share of IBM costs or how many of them are being traded . . . That world exists. It’s called the over-the-counter derivatives market. Five of the country’s biggest banks [ ] account for more than 90 percent of the market, where swaps of all shapes and sizes are traded more or less completely in the dark.”

Congress drafted legislation to bring derivatives out into the open, which the Senate gutted this spring. Notes Taibbi, “The Senate [functions] as a kind of ongoing negotiation between public sentiment and large financial interests.”

Folks, we are getting clobbered here. The Wall Street giants don’t want us to make money the old fashioned way in stocks, by buying good companies at a fair price. They want trades, lots and lots of trades. And they want derivatives, where they can gamble all day and make lots and lots of money.

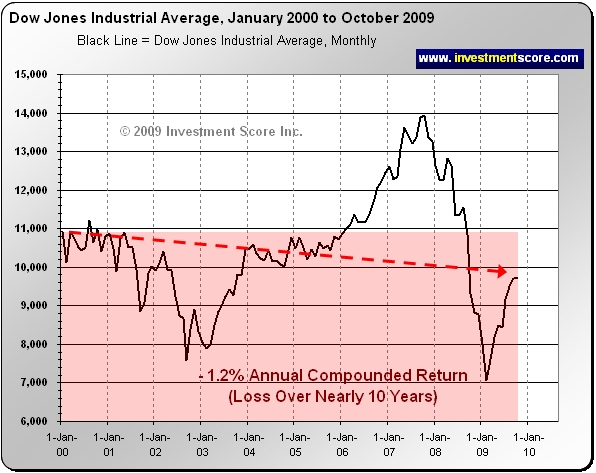

Traditional investing look like a bad play until there is fundamental change in the markets. Derivatives must come out into the open. America just suffered a “lost decade” in which the market declined over a 10-year period, just like happened previously in Japan. Your 401k money is a pawn, and we are all losing while the big players just get richer and richer.